Could Heavy Drinking Cause Dementia?

A leading cause of disability in people aged 60-years and older, dementia continues to be a prime focus of medical research. Studies are continually being conducted to determine causes of dementia to aid in establishing prevention and treatment methods.

A leading cause of disability in people aged 60-years and older, dementia continues to be a prime focus of medical research. Studies are continually being conducted to determine causes of dementia to aid in establishing prevention and treatment methods.

This is a daunting task, in part due to there being several types of dementia, from Alzheimer’s disease to vascular dementia and other types that are less common. It is not unusual for a patient to have multiple forms of dementia at the same time. And while the causes of dementia are still being determined, lifestyle changes that could reduce the chance of a developing this condition have been a research focus.

In an effort to analyze the association of heavy drinking to dementia, a recent study – the largest of its kind – published in The Lancet Public Health in March 2018 has found alcohol use is the biggest risk factor for dementia. Previous studies, the researchers explain, have pointed to an association between alcohol use and cognitive health, and some suggest that there is a “possible beneficial effect of light-to-moderate drinking. However, moderate drinking has been consistently associated with detrimental effects on brain structure.” But in this large-scale data review, it was indicated that heavy drinking may be related to dementia risk, regardless of the type.

What defines “heavy” drinking? The World Health Organization and the European Medicines Agency define heavy drinking as: drinking at least 60 grams of pure alcohol per day for men and at least 40 grams for women. Still not sure how that measures up? According to the U.S. National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, one “standard” drink contains roughly 14 grams of pure alcohol, which is found in:

- 12 ounces of regular beer (usually about 5% alcohol)

- 5 ounces of wine (usually about 12% alcohol)

- 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits (usually about 40% alcohol)

There are numerous reasons that heavy drinking has negative effects:

- Ethanol is known to have a direct neurotoxic effect and is linked to permanent structural and functional brain damage.

- Heavy drinking is also related to thiamine deficiency which can lead to Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome.

- Heavy drinking has been associated with vascular risk factors (such as high blood pressure, hemorrhagic stroke, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure).

- Tobacco smoking, depression, and low educational attainment, also potential risk factors for dementia, are associated with heavy drinking.

In light of these combined factors, there has been some discussion within the medical community as to whether there should be a specific diagnosis for alcohol-related dementia. However, even as recent as the widely-recognized Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care in 2017, alcohol use was not mentioned as a risk factor.

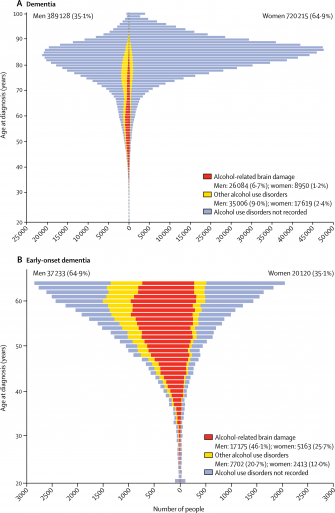

Research, however, is continuing to take a closer look at this serious health concern. A recent report released by French researchers examined the possible link between alcohol use disorders and dementia for males and females respectively, with a focus on early onset dementia (<65 years). They surveyed 2008-2013 discharge data for patients over the age of 20 archived in the French National Hospital Discharge database (Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d’Information), which contains all public and private claims for acute inpatient and day-case hospital admissions, post-acute care, and psychiatric care.

For the purpose of the study, onset was defined as the date of first diagnosis and early onset was defined as first diagnosis prior to age 65. These were then sorted into 3 groups: alcohol-related brain damage, vascular dementia and other types. To focus in the study, roughly 3.5% of the subjects were excluded due to the present of diagnoses of diseases that in and of themselves can increase or confound dementia diagnosis.

Of the 30+ million discharged, almost 1,000,000 patients had a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder, of whom 86% qualified for alcohol dependency. Alcohol-related brain damage was reported in over 35,000 dementia cases and almost 53,000 of other alcohol use disorders. These 2 conditions were most common in men (74.5% with alcohol-related brain damage and 66.5% with other alcohol use disorders) and explained 56.6% of early onset dementia cases. Alcohol use disorders showed up in 6.2% of the men, but in 16.5% of men with dementia making alcohol use disorders the “strongest modifiable risk factor for dementia onset in men.” Additionally, alcohol-related dementia tended to have earlier onset compared to other types.

Women tended to have delayed onset age and a lower overall occurrence of dementia than men up to the age of 80. This may be in part that, with the exception of depression and hypothyroidism, all independent risk factors for dementia including alcohol-related brain damage, were significantly less common among women. While the total number was lower than that of men, the association between alcohol-related brain damage and dementia was similar. Therefore, alcohol-related brain damage was the strongest modifiable risk factor for dementia for both men and women. When compared with other analyses of older populations, “alcohol use disorders remained strongly associated with late-onset dementia.”

Researchers concluded that the impact of alcohol usage on dementia is “much larger than previously thought”. Additionally, while risk factors like age and family history cannot be altered, other risk factors can be altered with effort. They determined that “alcohol use disorders were the strongest modifiable risk factor for dementia onset.”

Researchers concluded that the impact of alcohol usage on dementia is “much larger than previously thought”. Additionally, while risk factors like age and family history cannot be altered, other risk factors can be altered with effort. They determined that “alcohol use disorders were the strongest modifiable risk factor for dementia onset.”

Additionally, these effects may not be reversible. While reducing intake to the level of abstinence lowers the risk of death overall, the study revealed that dementia onset remained unchanged. This supports other studies which found alcohol usage “directly exerts lifelong brain damage.” Lastly, they concluded that alcohol use disorders contribute to risk of dementia in a myriad of ways due to their association with other risk factors.

Based on their findings, they propose that alcohol use disorders be acknowledged as a major risk factor for all types of dementia and as a main cause of early-onset dementia. They also advise health care practitioners to be more aware of alcohol usage over the patient’s lifetime as this seems to be commonly overlooked. Early detection and treatment of less severe alcohol use disorders may have great importance for long term health.

Being responsible in how you include alcohol in your diet can have a significant impact on your health now, and for years to come. Your use or abuse of alcohol has the potential to impact your physical, social and mental health. It is important to be aware of your alcohol consumption. Do not allow alcohol addiction to take control of your life.

If you or a loved one has a problem with alcohol addiction, seek help sooner rather than later. As research is finding, the health concerns are numerous and severe. Heavy drinking could progress from not remembering the night before, into not remembering the names of your loved ones. Assistance is available 24/7, 365-days-a-year. You may call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or the REDLINE at 1-800-889-9789, which is Tennessee’s toll-free referral and information line to assist persons with an addiction in locating help.

Take care of yourself with proper nutrition and healthy levels of activity. Take control of risk factors in your life that you have the power to change. Your doctor of chiropractic is an excellent source of information about proper nutrition and wellness. Looking at your whole health, your chiropractic physician can also help you understand how alcohol fits into your overall dietary concerns. Find a doctor near you by clicking here.

_________________________________________________________________________

REFERENCE: Contribution of alcohol use disorders to the burden of dementia in France 2008–13: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Michaël Schwarzinger, MD, Prof Bruce G Pollock, MD, Omer S M Hasan, BA, Carole Dufouil, PhD, Prof Jürgen Rehm, PhD. QalyDays Study Group. The Lancet Public Health. Volume 3, No. 3, e124–e132, March 2018.