Research News: A Closer Look at Acute to Chronic Low Back Pain

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common complaints around the world. While extremely prevalent, acute LBP is often brushed off as a fleeting condition. It is assumed that most people’s pain will resolve with little to no intervention within a few weeks. Patients are often encouraged to keep moving as best they can and basically wait it out.

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common complaints around the world. While extremely prevalent, acute LBP is often brushed off as a fleeting condition. It is assumed that most people’s pain will resolve with little to no intervention within a few weeks. Patients are often encouraged to keep moving as best they can and basically wait it out.

However, research is showing that this blanket advice may be leading to higher and higher rates of acute LBP transitioning to chronic LBP. Once the condition becomes chronic, all too often it also becomes a disabling and expensive condition. In fact, LBP is the single largest cause of disability in the US, garnering twice the burden of any other health condition. Treatment for LBP and related disorders are now the most expensive medical problem in the US, with most of the costs accumulating in the ambulatory care settings such as primary care.

Modern medicine has had an explosion of knowledge in the last several decades. Improvements in technology have allowed researchers to delve more deeply into the how’s and why’s of the human body and fine tune our standard knowledge base. \

In recent years, researchers have begun to question the “fleeting” quality of “acute low back pain”. When other factors, such as return to work, are included in a study, it becomes evident that the development of chronic pain may be significantly underestimated. Additionally, a recent JAMA study noted that prognoses for acute LBP in primary care settings transition to chronic LBP may range as much as 2%-48%.

Historically, a lack of a single specific diagnosis definition has contributed to the confusion. Therefore, the National Institute of Health (NIH) Task Force Pain Consortium was convened and charged with developing a standardized definition and research standards for chronic LBP which were then published in 2014.

Along with the definitions and standards, the NIH Task Force also recommended additional study of prognostic instruments, such as the Subgroups for Targeted Treatment (STarT) Back tool (SBT). The SBT is a 9-question survey which can be administered quickly and easily to patients. It is designed to help providers detect which patients may be at higher risk for poor functional outcomes and has been proven effective in this. As such, it may also be used to help guide providers in their treatment decisions. Clinical guidelines’ recommendations include reassurance that most episodes resolve quickly, with low risk of a serious problem, along with advice to remain as active as possible.

In 2017, The Annals of Internal Medicine published an updated Clinical Practice Guideline for Managing Low Back Pain from the American College of Physicians. In the full guideline titled, “Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline”, authors reviewed studies related to non-surgical treatments for adults with low back pain including the use of medications as well as other noninvasive treatments. Based on this literature review, they determined “Surgery is rarely needed for patients with low back pain.”

Among the recommendations: Implement spinal manipulation and postpone pharmacologic management. For most patients with acute (pain lasting less than 4 weeks) and subacute (pain lasting 4-12 weeks), they recommend clinicians and patients initially choose nonpharmacologic treatment such as: heat therapy, massage, acupuncture and SPINAL MANIPULATION.

They recommend that medications such as ibuprofen or muscle relaxers be discussed only if these treatments do NOT work. In the absence of red flags, delaying initial use of diagnostic imaging, specialty consultation and prescription of opioid medications, allows time for the body to heal via more natural processes.

Study authors point out that nonconcordant care, (care which does not follow these guidelines) can “lead to direct and indirect harm, given that it has been linked with medicalization and unnecessary health care utilization.”

Recently, researchers set out to determine the link between the transition from acute to chronic LBP with (1) their SBT risk scores, (2) demographic, clinical, and practice characteristics; and (3) guideline nonconcordant processes of care. They developed an inception cohort study was conducted alongside a multisite, pragmatic cluster randomized trial.

Study participants were adult patients with acute LBP enrolled in 77 primary care practices in 4 regions of the US. Initial visits occurred between May 2016 and June 2018. SBT was administered at baseline and patients were assessed for chronic LBP at 6 months. The NIH Task Force definitions were utilized for the study. Final follow-up was completed by March 2019. If a patient displayed any red flags for serious underlying reason for their pain (fever, fracture, cancer, etc.) they were excluded from the study.

The results revealed a disconnect between the guidelines and the treatment administered to patients.

Within the initial 21 days of the first visit:

- Almost 1/3 (30%) of patients received prescriptions for non-recommended medications

- Of those, over half (65%) were for opioids!

- Almost ¼ (24%) received an order for x-ray, CT scan or MRI

- 6% were referred to a medical specialist, of which 62% were surgeons.

Overall, the 6-month rate of acute to chronic LBP transition was 32%.

By risk category:

- Low risk 19%

- Medium risk 33%

- High risk 49%

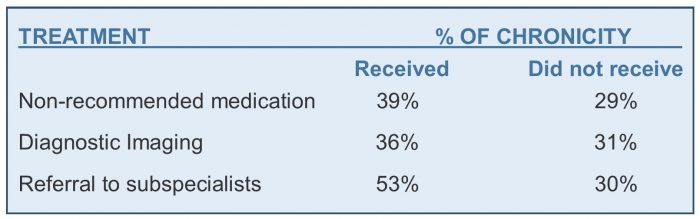

Additionally, there were increases in the transition to chronic LBP that aligned with nonconcordant treatment.

Patients who received 1 or more nonconcordant processes of care had incrementally higher odds of developing chronic LBP:

- Overall rate for patients with 0 nonconcordant treatment 27%

- Overall rate for patients with 1 nonconcordant treatment 35%

- Overall rate for patients with 2 nonconcordant treatments 46%

- Overall rate for patients with 3 nonconcordant treatments 53%

These findings corelate with an earlier study of study of the treatment of back pain from 1/1/1999-12/26/2010. Interesting points from that study included:

- Early MRI for acute back pain was associated with an 8-fold increased risk of surgery

- A 50% decrease in first-line NSAID or acetaminophen use was accompanied by a 8% increase in narcotic prescriptions,

- There was a 106% increase in referrals to other physicians.

- Spending for back pain and related conditions increased faster than overall health spending from 1997-2005.

Just as the SBT has been shown to predict poor functional outcomes, this study showed it may also be a reliable predictor of chronicity.

The odds ratio of developing chronic LBP was 1.59 times higher for those in the medium risk category when compared to the low-risk group. For those in the high-risk group, the odds ratio jumped to 2.45 times higher!

Other factors that were associated with an increased risk for acute LBP to transition to chronic LBP include: baseline disability, (with more severe disabilities being associated with even higher risk for chronicity), health insurance, body mass index, smoking status, diagnosis at initial visit, and psychological comorbidities.

Researchers concluded that the overall transition to chronic LBP was 32%. They found strong associations with both baseline SBT and whether or not the patient was treated according to the latest guidelines or not. They also concluded that “the transition from acute to chronic LBP is much greater than historically appreciated, the SBT can estimate risk of transition, and lack of guideline adherence may increase transition rates.”

They acknowledge that it is easy to focus on treating high-risk groups, but point out that well over half, 60%, of the patients who became chronic began in the low and medium risk groups. Therefore, applying the same minimalist treatment for all patients presenting with acute LBP may result in less than adequate care. However, going in the opposite direction and treating with medications and referrals to subspecialties across the board is unwarranted, wasteful of resources, and can, itself, lead to inappropriate care and increased risk of chronicity.

Sadly, despite additional research adding to the body of knowledge on this topic, and numerous issuances of guidelines and recommendations, these and other recent studies show that not only are many providers not following the most up to date information, but also that the nonconcordant care may be contributing to patients transitioning from acute care to chronic care.

Due to the speed of new information being generated various care standards, recommendations and guidelines are constantly being updated. An editorial published in Maturitas, an International Journal of Midlife Health and Beyond, notes that while most research and guidelines are developed by specialists, most patients are seen in primary care settings. Further, they estimate that “average family physician would need 18 hours per day to follow the volume of recommendations for chronic disease and preventive care” – not at all realistic. They also noted that “most guidelines lack specific content or tools that allow clinicians to help their patients make informed choices,” which puts health care providers in an impossible position.

Together these factors suggest that there may be a need to develop LBP guidelines that include some type of risk stratification tools, to enable providers to recognize those at high risk of chronicity and treat them accordingly, without being too aggressive and overutilizing resources. For providers being asked to provide more results without clear direction for how to do that, tools such as the SBT can be invaluable in sorting out risk factors and treating each patient with the care that is most beneficial to that individual patient.

Identifying the appropriate treatment to address the pain and prevent chronicity, for each individual patient is very important. This allows, not only for better care for that individual, but also a significant savings in resources and overall financial cost savings for the health care system.

So how can this happen? It has been noted with other conditions, that including nonphysician health professionals (eg, nurse practitioners or physician assistants) to assist in care management may improve guideline adherence. This reduces overall caseloads and allows for each provider to have more time with each patient and still have time left to learn about new developments in treatment.

An alternative model that has proven to be effective, is to have chiropractors as the initial or early point of contact for LBP patients. With extensive clinical training in the musculoskeletal system and LBP specifically, they are uniquely positioned to aid patients with the evidence based conservative care that is currently strongly recommended in guidelines. Additionally, chiropractors are trained to identify patients who do require additional medical care and can not only refer those patients to other health care providers, but also collaborate with those providers to provide the most effective and lowest risk treatment possible.

One more option is that of the multi-disciplinary practice. Rather than a chiropractor referring to a medical doctor, or vice versa, a group of various specialties are in practice together, allowing the patient to receive the needed care all in one place. Because the providers work together, often in the same location, it can make coordination of care easier and more efficient for both patient and providers.

LBP management is just one of the areas where chiropractors excel in patient care! If you or a loved one are experiencing low back pain, try #chiropractic1st. Whether you visit a single provider office, a group, or a multi-disciplinary office, chiropractic care can help you keep moving with safe, natural care that works and helps you move past this episode of pain successfully and resume regular activities more quickly.

REFERENCES:

Stevans JM, Delitto A, Khoja SS, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Transition From Acute to Chronic Low Back Pain in US Patients Seeking Primary Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037371. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37371

Day CS, Yeh AC, Franko O, Ramirez M, Krupat E. Musculoskeletal medicine: an assessment of the attitudes and knowledge of medical students at Harvard Medical School. Acad Med. 2007 May;82(5):452-7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803ea860. PMID: 17457065.

Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE. Worsening Trends in the Management and Treatment of Back Pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1573–1581. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8992

Mehling WE, Gopisetty V, Bartmess E, Acree M, Pressman A, Goldberg H, Hecht FM, Carey T, Avins AL. The prognosis of acute low back pain in primary care in the United States: a 2-year prospective cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 Apr 15;37(8):678-84. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318230ab20. PMID: 22504516; PMCID: PMC3335773.

Online STarTBack Calculator https://startback.hfac.keele.ac.uk/training/resources/startback-online/

Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, Andersson G, Borenstein D, Carragee E, Carrino J, Chou R, Cook K, DeLitto A, Goertz C, Khalsa P, Loeser J, Mackey S, Panagis J, Rainville J, Tosteson T, Turk D, Von Korff M, Weiner DK. Report of the NIH Task Force on research standards for chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2014 Jun;15(6):569-85. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.03.005. Epub 2014 Apr 29. PMID: 24787228; PMCID: PMC4128347.

Allen, G. Michael; McCormack, James P; Korownyk, Christina; Lindblad, Adrienne J.; Garrison, Scott; Kolber, Michael R.; “The future of guidelines: Primary care focused, patient oriented, evidence based and simplified” Maturitas VOLUME 95, P61-62, JANUARY 01, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.08.015